To end the HIV/AIDs epidemic, we first need to end the inequalities that prevent people from accessing healthcare. With support from the Global Fund, Cordaid runs a programme in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) that takes a Gender and Human Rights approach to ensure HIV services are accessible for all.

Since the first case of AIDS globally in 1981, and the discovery of its cause, the HIV retrovirus, in 1983, great strides have been made to eradicate the epidemic. After four decades of relentless efforts against HIV, 94,000 people are still living with AIDS in the DRC. Today, the epidemic is said to be “concentrated”. This means that despite the decline in the prevalence of HIV in the general population, there is a concentration of the epidemic in specific groups.

Discrimination is a barrier to healthcare

Too often, those most affected by HIV are the same people who don’t have access to healthcare. Discrimination, gender inequality, poverty, and criminalisation are all barriers that can prevent them from accessing healthcare. As a result, HIV disproportionately affects so-called “key populations”. These include sex workers, transgender people, men who have sex with men, people living in prisons, and people who inject drugs.

“There is a lot of discrimination against key populations,” explains Dr. Guy Mukari, Cordaid’s programme coordinator based in Kinshasa. “It happens that health centres stigmatise them or even refuse to provide care. Too often people feel that they cannot come forward to test themselves or seek treatment because of fear of being stigmatised even further.”

“We [people identifying as LGBTQI+] experience aggression and transphobia. They give themselves the right to physically attack us.”

Cordaid’s programme focuses on strengthening the health system to remove stigma and social justice barriers and ensure key populations have access to adequate HIV services. With the support of the Global Fund, and in partnership with the Congolese Ministry of Health, we work with human rights hubs, health centres and community centres in 24 out of the 26 provinces of the DRC.

Care services that work for everyone

Social justice barriers directly affect the health of these key populations. They also jeopardise the capacity to control the epidemic, in the DRC as well as globally. “Until we address discrimination, gender inequality, and other barriers, and ensure these discriminated groups of the population have access to HIV services, we will not succeed in eradicating the epidemic”, explains Dr. Mukari. “This underscores the need to scale up efforts and address the social injustices that prevent many people from accessing HIV services.”

According to Dr. Mukari, “programmes need to be adapted so that necessary services both in terms of prevention and care, reach the most affected parts of the population. This way we make sure that every individual has easy access to prevention methods and care services that work”.

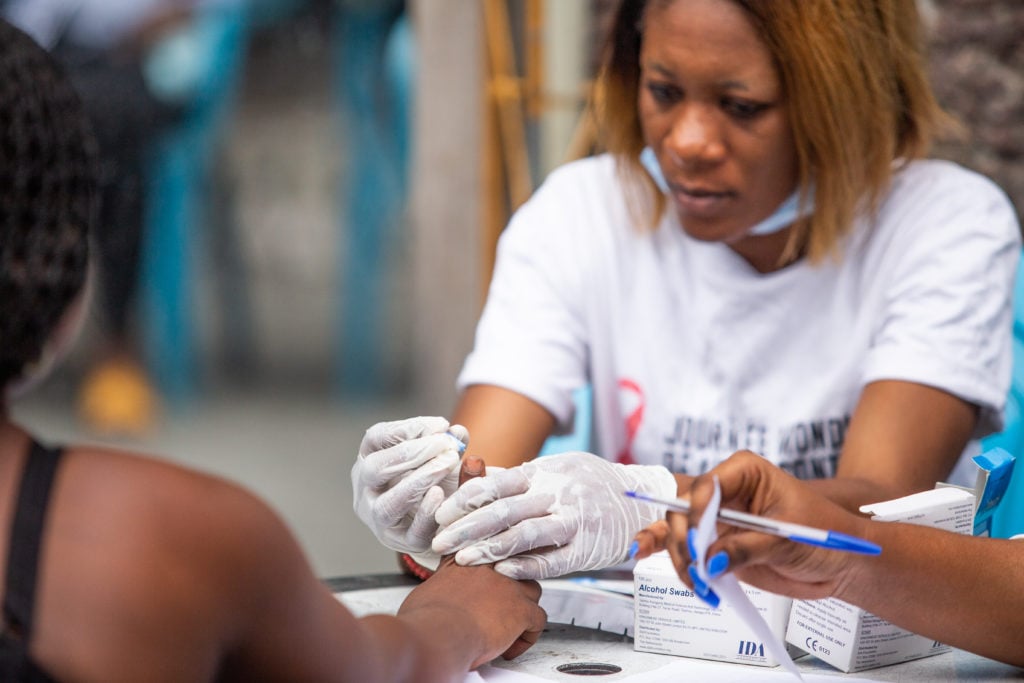

In the DRC, Cordaid’s programme works both on prevention (testing services, awareness raising, and education), and on patient care (treatments, patient follow-up, and legal services). At the heart of this programme are the communities and the people living with HIV. They actually run a lot of the activities. To make sure that social justice barriers are effectively addressed, the programme also includes a Gender and Human Rights approach.

Reaching key populations through a community-led approach

Cordaid reaches out to key populations by working with community-led centres. These are welcoming environments where services are adapted with a community approach to support key populations. They receive specific quality services and care, and awareness is promoted by peer educators, often people also living with HIV.

With support from the Global Fund, in 2021 we were able to test over 3 million people for HIV, including close to 120 thousand people from key populations.

Juive, a counsellor with our partner PASCO, works closely with key populations. “Part of my work is informing people who are most affected by HIV”, she says, “including sex workers and people of the LGBTQI+ community, about how to prevent infections and the benefits of getting tested. In addition, we organise safe-spaces for HIV-positive women to share their stories and learn from each other’s experiences.”

For Juive, working with key populations makes a difference. “I started to notice more awareness about the importance of using protection. Our programme helps them in many ways”.

A gender and human rights approach to health

Cordaid also works with Gender and Human Rights hubs. These hubs ensure key populations have easy access to holistic care and services, free from stigma. There, people living with HIV can seek medical, mental health, and judicial support. The human rights aspect of improving access to healthcare is essential if we are to eradicate the HIV epidemic.

Too often, for members of the LGBTQI+ community, their access to healthcare is being cut off by discrimination and violence due to their gender identity, expression, or sexual orientation. As Pete explains, a visitor of the Gender and Human Rights hub, “we [people identifying as LGBTQI+] experience aggression and transphobia. People can come to look at us and not appreciate the way we look. They give themselves the right to physically attack us.”

For Pete, having a hub that provides holistic care that includes legal counselling means that they have the tool to fight against gender-based violence. “Today, thanks to the information and awareness on human rights, and knowing my rights, I went directly to the lawyer assigned by the hub that defends our rights after my last aggression, and made a complaint to the police. The aggressors are going to justice.”

Treatment saves lives. Outreach provides opportunities for more key populations to be tested, especially those who face discrimination and other barriers to accessing health services. With the support from the Global Fund, in 2021 this programme was able to test over 3 million people for HIV, including close to 120 thousand people from key populations. Over 200 thousand people living with HIV now have access to antiretroviral treatment.

Getting back on track in the fight against HIV/AIDS

But many challenges remain. With the COVID-19 pandemic, HIV testing dropped by more than 22% in most countries, delaying HIV treatments that could save lives. Now more than ever, the world should scale up efforts to get us back on track in the fight against HIV/AIDS. This is why Cordaid works with organisations like the Global Fund because they #FightForWhatCounts.

And tackling social barriers and injustices is vital to effectively address the HIV/AIDS epidemic across the globe.

This article was written by Madeleine Matayo Safi (Cordaid communication officer in Kinshasa) and Adriana Parejo Pagador (Cordaid communication officer in The Hague)