Cordaid has been the agency for technical assistance in improving the primary education system in the Democratic Republic of the Congo for three and a half years. “The quality of education as well as the parent and pupil satisfaction rates significantly increased in the schools we worked with”, Cordaid’s education expert Paula Mommers points out. The vice-minister for education is impressed by the results and would like to scale up the programme if funds are available.

In 14 provinces, between May 2018 and December 2021, Cordaid introduced the method of performance-based financing (PBF). We trained teachers of 1,350 primary schools and employees of the decentralised structures of the ministry of education, among which the school inspectors.

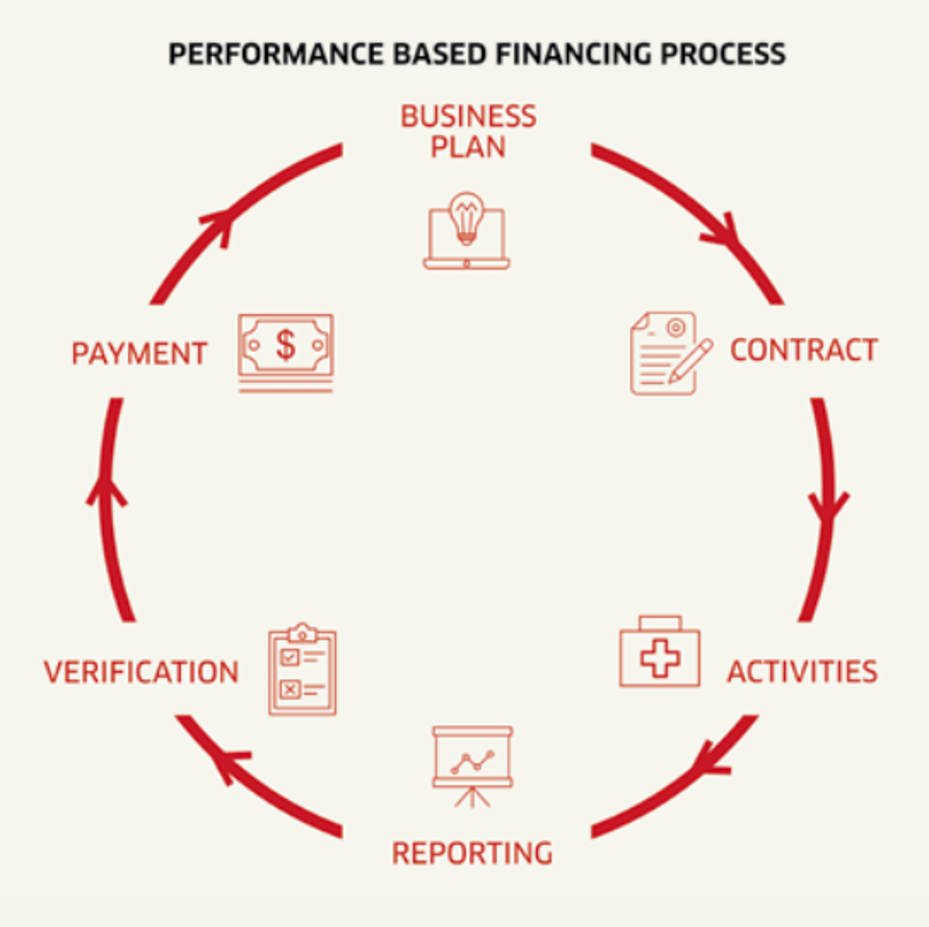

In short, the PBF method entails that the contracted schools and decentralised structures receive payments after pre-defined results have been verified and validated. These funds can then be used to top up salaries and improve the quality of education and infrastructure.

The project was part of PAQUE (Projet d’Amélioration de la Qualité de l’Éducation) and received funding from the Global Partnership for Education, managed by the World Bank.

Challenges

The support helps teachers, pupils, parents and educational authorities in dealing with some of the many challenges they face. This includes low teacher salaries (between 100 to 200 euros a month on average, if paid at all), crowded classes (50 pupils per class is a national standard, but in reality 80 is not exceptional), and a lack of infrastructure and educational material.

Also, the COVID-19 pandemic and the insecurity in conflict-ridden areas, such as the Kasai provinces, pose serious problems to the educational system.

In 2019, the government abolished primary school fees, making it easier for parents with low incomes to send their kids to school. Unfortunately, the costs of school uniforms, transport and materials, would still inhibit many children from attending school.

Improvements

“Our PBF strategy incentivised schools and civil servants, like school inspectors, to improve the quality of and access to their services”, Mommers explains. This is a complex operation, involving performance contracts with every single structure, training, result verification and validation and the triannual payment of subsidies.

Schools received a triannual subsidy based on achieved results for selected indicators. These included teacher attendance and punctuality, the number of pupils with specific attention to the number of girls attending, the number of retrieved pupils that risk dropping out, and the presence of latrines and drinking water. Mommers: “These are typical indicators meant to improve the governance and cohesion of a school.”

In the three and a half years the programme ran, the education quality of the 1,350 participating schools went up from 46% to 84%. This significant increase was partly achieved through infrastructural improvements (better-built classrooms, improved gender-segregated latrines, and school fencing), the acquisition of benches, textbooks and other materials, the improvement of teaching methods and the reduction of teacher absenteeism.

A teacher in the village of Yakoma said: “Lesson preparation, punctuality and attendance are among the PBF indicators. During the project, most teachers seriously improved their preparation and the content of their lessons.”

Parent-school collaboration

One result indicator dealing with the collaboration between schools and parents was the number of times parent committees and teachers paid joint home visits to pupils at risk of dropping out. “The efforts to keep children in school had an impact”, according to Mommers. “Within the project period, the school recovered over 80% of the children at risk of dropping out. And the presence of other children who need special attention increased from 84% to 98%. The number of girls attending, which is an indicator by itself, went up from 218.000 to 300.000.”

There are more successful examples of the involvement of parents in school governance. The parent committee of Bisende Primary school, in Central Kasaï Province, wanted to reduce the number of pupils per class, which was 81 on average. With the PBF subsidies, parents and teaching staff built six new classrooms.

Scaling up the PBF approach

During the PBF programme in South Kivu, from 2007 until 2017, representatives of the national government visited several times. They were impressed by the results and the programme was scaled up to 14 educational provinces as part of the PAQUE project.

Recently, in a PAQUE meeting, Madame Aminata Namasia Bazego, the Vice-Minister of Education, reiterated her hope “to see the PBF approach implemented in all educational sectors”. She called upon all parties within the education system “to scale up PBF to improve services and to reach the goals we have set”.

Now that Cordaid’s involvement in the current PAQUE project has come to an end, Mommers hopes for future investment efforts. “We all know education is a foundation for life. Good education increases the chances of finding a job and getting an income. For future farmers, it means they will be in a better position to negotiate fair prices. Girls who go to school and get their degrees will have children later in life and will have fewer of them. These are just some examples of the priceless value of education. We can only hope the government will continue the PBF approach, with funding from donors, and will expand it to all primary schools in the country.”