“No one is safe until everyone is safe”, says Seth Berkley, CEO of GAVI, The Vaccine Alliance. As the world entered a third year marked by COVID-19, let us reflect on the global collective actions against the spread of the virus. What have we learnt? And what should be done now?

As part of Cordaid’s work on strengthening health systems, Cordaid partners with GAVI and COVAX – the global vaccine-sharing initiative co-led by GAVI – to ensure vaccines are accessible for everyone, everywhere. Cordaid’s senior Health Expert, Jos Dusseljee, reflects on the global COVID-19 response so far and argues for a health system approach to bring the COVID-19 pandemic to an end.

Where are we now in the fight against COVID-19?

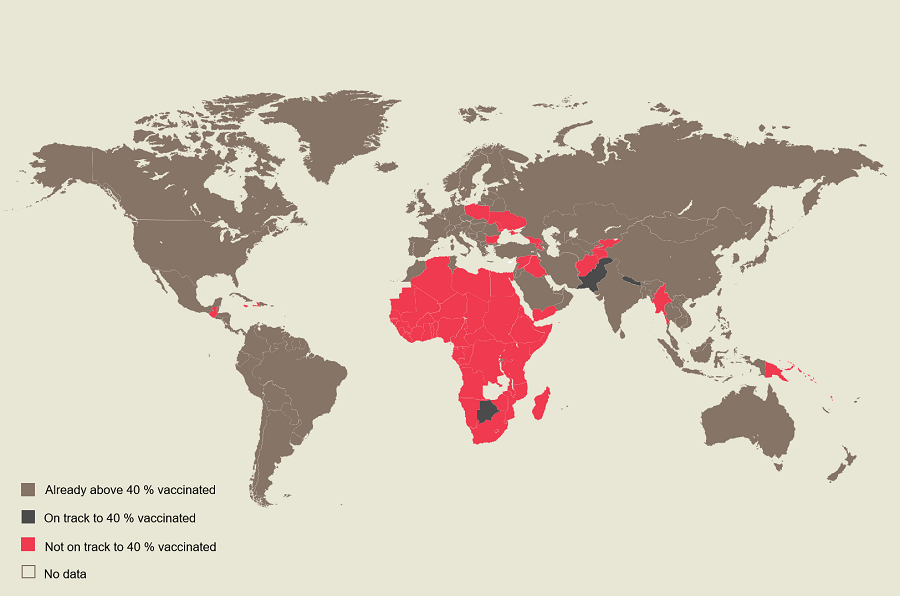

More than a year after the first COVID-19 vaccine shot was administered, over 60% of the world population has received at least one dose of vaccine against COVID-19. Collectively, more than 11 billion doses have been manufactured, of which 10 billion have been administered, enough doses to vaccinate most of the world’s adult population by now. It goes without saying that, in the past two years, we have witnessed collective action on unprecedented scales. But we have by no means stopped COVID-19.

“What we saw in the past two years is a terrible disparity between high- and low-income countries, in terms of access to vaccines and other health resources. These inequalities arising during the pandemic are part of a dangerous trend that is not exclusive to COVID-19 vaccines”, observes Jos.

The COVID-19 pandemic tells the story of historic and systemic global inequalities. While 72% of the population of high-income countries have received at least two doses of COVID-19 vaccines, only 6% have in low-income and war-torn countries. Scientists have for long warned that leaving large parts of the world unvaccinated provides a fertile environment for dangerous variants to arise.

And while several countries have pledged to donate vaccines through COVAX in 2021, these donations are far from being enough to end COVID-19. With each new variant, we may fear “inequity 2.0”, says Seth Berkley in an interview with AP News, “where we see wealthy countries hoard those vaccines once again as we saw at the beginning of the pandemic”. Indeed, contributing donors, like the Netherlands, are increasingly not delivering doses to COVAX as planned, amid fears of the Omicron variant, and are instead launching booster programmes.

Since the Omicron variant became dominant, rich countries have given out more vaccine boosters in the space of four months than poor countries have received in one year. Boosters cannot be the long-term solution, and are certainly unsustainable, with the next booster to be expected shortly, as announced by the Netherlands and Israel.

Vaccine dumping, a devil in disguise

Low-income countries continue largely to depend on vaccine donations from high-income countries to immunise their population. One of the reasons behind this dependency is the intellectual property rights over COVID-19 vaccines enabling pharmaceutical companies to reap millions in profit while maintaining manufacturing knowledge and technology themselves. From the way pharmaceutical companies have behaved, one conclusion can be drawn: profit is a primary concern, and global health is still a secondary concern.

“If someone is giving you vaccines that are going to expire in less than three months, that is dumping. It’s not a donation anymore”

Experts have identified several barriers preventing a successful global vaccination initiative: vaccine hoarding by high-income countries, delivery delays from pharmaceutical companies to African countries, slow in-country rollouts, and importantly, short shelf-life vaccines received by low-income countries from donating countries.

These inadequate donations from contributing countries give rise to scepticism from low-income countries to accept vaccines donated through COVAX. “If someone is giving you vaccines that are going to expire in less than three months, that is dumping. It’s not a donation anymore,” explains Dr Ahmed Ogwell Ouma, deputy director of the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, in an interview with Devex. “It’s going to expire in your hands if you don’t have a system that is ready to be able to absorb it”.

As a result, huge amounts of funds and vaccines will continue to be wasted if donating countries do not adhere to certain minimum standards and will instead become medical waste to be managed by low-income countries.

Instead of effectively supporting low-income countries to respond to COVID-19, the practice of vaccine dumping may cause more harm than good. Vaccines are being dumped without enough shelf-life, announced without enough time for receiving countries to prepare, or even without the necessary vaccination supplies such as gloves, syringes, needles and diluents. And where the additional vaccination supplies are not provided, they will be sourced from funds that were meant to support primary health care services.

“Vaccine dumping can run the risk of stretching health systems in low-income countries,” explains Jos, “where mortality from preventable diseases, such as malaria and tuberculosis, is already rising because of the burden of the pandemic on health systems”.

“Without aiming for vaccine equity, and strong health systems everywhere, the world will not deal successfully with this pandemic.”

From vaccines to vaccination

In a joint statement, GAVI – who is co-leading the COVAX initiative – declares urgent the need for contributing donors like the Netherlands to adhere to essential requirements for an effective vaccine-sharing mechanism that does not increase the burden of already stretched health systems in low-income countries. By the end of March 2022, GAVI aims to raise $5.4 billion to launch COVAX’s second year of efforts to end COVID-19 and overcome the challenges faced in 2021. Ending COVID-19 involves more effort than donations. This new phase of efforts of COVAX aims to not only continue progress towards vaccine sharing but also to step up financing for vaccination supplies and to support in-country delivery systems.

Strong health systems to end COVID-19

According to Jos, “without aiming for vaccine equity, and strong health systems everywhere, the world will not deal successfully with this pandemic. Nor with any other future global pandemics for that matter. The only real answer is to invest in making health systems stronger in all parts of the globe”.

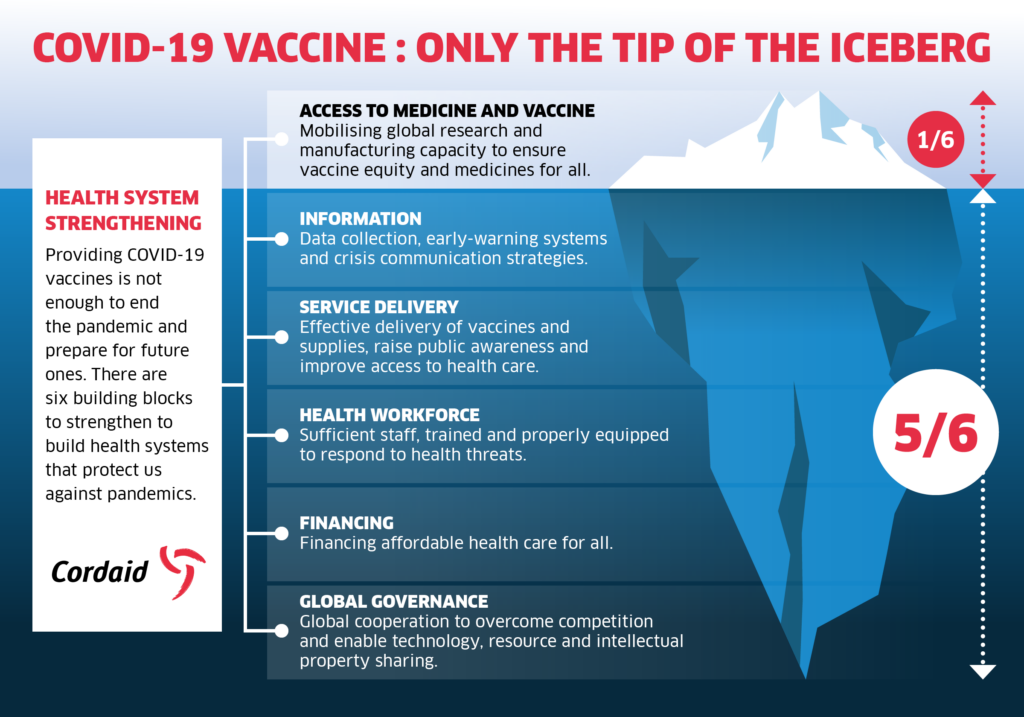

Vaccine donations not only require consideration for long-enough shelf-life, but also financial investments in health systemic efforts. This includes investments in the six ‘building blocks’ that make up health system strengthening. When it comes to epidemics and pandemics, it is important to adopt a holistic approach where each of these blocks is addressed in order to end COVID-19 and prepare for future pandemics.

“Low-income countries need strong health systems to face COVID-19”, argues Jos, “and vaccine donations are just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to what is needed to bring an end to COVID-19 and prepare against future pandemics”. As Cordaid’s health experts recently stated, drawing lessons from the long fight against HIV and AIDS in the 80s and 90s: we must raise our global ambitions.

We, the international community, must tackle vaccine inequity and make global health a primary concern. A focus on profit and the ensuing global inequalities is not the answer. Because no one is safe until we are all safe.