In Erbil, capital of the Kurdistan Region in Iraq, Cordaid uses a results-based financing approach to improve policing and GBV responses as well as police-community relations. “The approach helps service providers to overcome their limitations, women to overcome their distrust, and communities to break seals of silence”, says Nikki de Zwaan, Cordaid’s expert on security provision and access to justice.

Increasing women’s sense of security in communities with a conservative gender role attitude is as necessary as it is dangerous. Just how dangerous – and necessary – is shown by the series of armed attacks on offices of the Directorate to Combat Violence against Women (DCVAW) in the Kurdistan Region in Iraq, a few years ago. Some of the attacks took place while VAW survivors were transferred to safe locations.

‘Increased responsiveness to the real needs of women and girls helps to restore trust in state structures. In conflict-affected societies this is a first and essential step towards stability.’

It is exactly these DCVAW offices in the Erbil Governorate of the Kurdistan Region Cordaid is now supporting, in a pilot project called Context Matters. DCVAW is a multi-sector law enforcement unit, part of the Ministry of Interior, and staffed mainly by police officers.

Restoring trust, first step towards stability

“To support 3 of the DCVAW offices, we use a results-based financing (RBF) approach”, says Nikki de Zwaan, Cordaid’s expert on security provision and access to justice. “We pay financial incentives after they have verifiably improved their handling of GBV cases and strengthened their relationship with communities. This, in turn, increases their responsiveness to the real needs of women and girls, but also men and boys. It helps to build or restore trust in state structures, which, in conflict-affected societies, is a first and essential step towards stability”, she adds.

Ideally, local authorities like the police, refer all GBV and VAW cases to the nearest DCVAW station. Here, they will investigate the case, and depending on its severity and the victim’s needs, come up with different forms of support. If a woman’s security and even her life is at risk, they will take her to a safe house (there’s one in Erbil, accommodating up to 10 clients). If possible, they will play an intermediary role in settling disputes with family members. And in cases of rape and other criminal offences, they will assist in filing a lawsuit.

‘There’s a fear to ask for help as well as a practice of sweeping scandals under the carpet. Sexual violence is still very much taboo. Society stigmatizes victims.’

The Kurdistan Region is one of the few areas in the MENA region with a law that criminalizes domestic violence. This reinforces DCVAW’s mandate. Unfortunately, a score of obstacles undermines the protections intended by the law.

Sweeping scandals and criminal offences under the carpet

“There are many reasons why people, especially women, do not find their way to the DCVAW”, explains sociologist Alwand Talaat, who coordinates Cordaid’s Context Matters project in Erbil. “Partly, DCVAWs limitations in performance account for that. But cultural practices and convictions stand in the way too.

There’s a fear to ask for help as well as a practice of sweeping scandals under the carpet. Sexual violence is still very much taboo. Society stigmatizes victims. There’s even a strong tendency to criminalize them, instead of criminalizing violations and perpetrators. Often, families take justice matters into their own hands, resulting in acts of revenge and honour crimes. Instead of increasing women’s security, this only leads to more violence and more insecurity”, Talaat continues.

Context Matters’ aim is to help curb this obstruction of justice and security. The first phase of the pilot in Erbil, which started last October, consisted of supporting DCVAW stations in assessing their own limitations and in mapping expectancies among communities. Dr. Izaddine Aziz, doctor of psychology at Salahaddin University in Erbil and involved in the project as a consultant: “This resulted in three sets of result indicators for improvement: performance indicators, indicators related to the internal workings of the unit and indicators of the DCVAWs community relations.”

Visibility is more than just a billboard sign

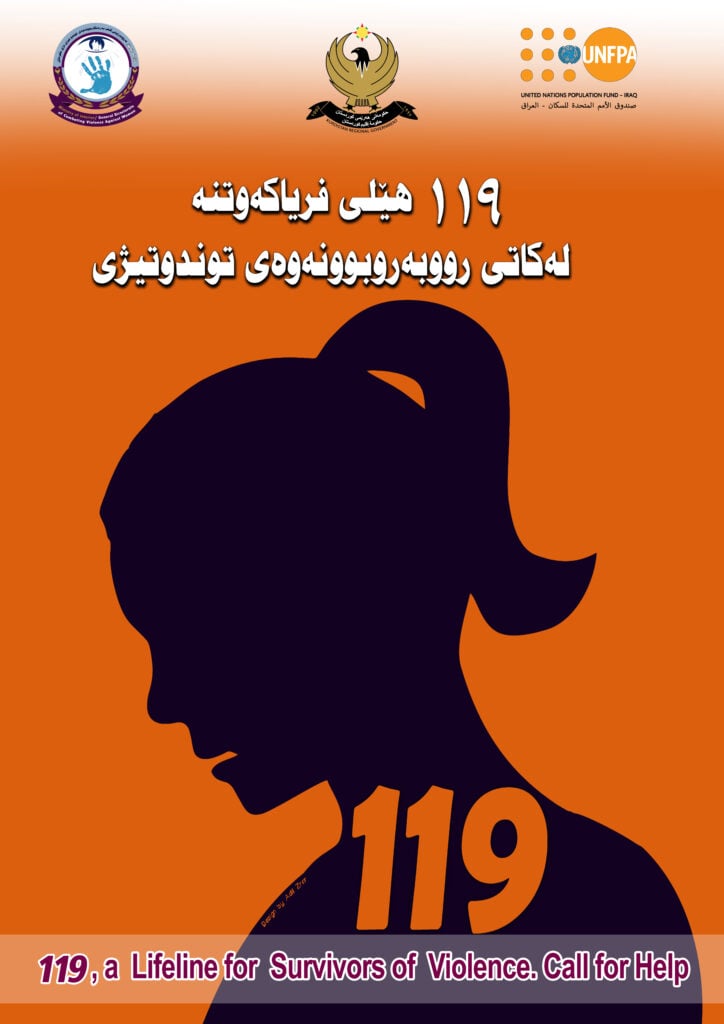

“As for community outreach”, Dr. Aziz continues, “DCVAW became aware during Context Matters sessions, that they had never proactively reached out to communities. Up till then having a billboard sign with their name on the station’s building and waiting for others to refer cases to them, had been their main idea of visibility and accessibility. Context Matters inspired them to organize community gatherings, raising both the awareness of GBV and of DCVAW’s services among citizens and of people’s needs and challenges among DCVAW staff. This was before corona hit the country. Today, DCVAW stations use social media, even television to enhance their visibility. The hotlines they opened greatly enhanced accessibility. Especially in the current corona lockdown situation. A lot of these results can be attributed to the Context Matters project.”

Community sessions took place among university and high school students, with community leaders who, in their turn, reached out to poorer, uneducated, and illiterate women and men of their communities. And with religious leaders, who, in pre-corona days, shared the sessions’ outcomes during Friday prayers at the mosque.

Confidentiality & integrity

Often, a rape victim who has the guts to formally press charges and wants to start a lawsuit is thwarted. Not so much by the unwillingness of public authorities such as the DCVAW, but by their dysfunctionalities and limitations. “Take the crucial concepts of confidentiality and integrity”, says Dr. Aziz. “When we started working together, it was clear that DCVAW officers did not fully grasp what length they needed to go to secure the confidentiality of their clients. There were no private rooms for interviews and case investigation. Staff members exchanged personal and confidential information. Today, all stations we work with have separate and privacy-proof interview rooms. Each case has one dedicated DCVAW officer. Hotline staff assures anonymity. All these privacy and confidentiality improvements have increased women’s and their families’ sense of security as well as their trust in DCVAWs services.”

When physical and mental integrity is at risk, which is always the case with gender-based violence, decisiveness is key. “Too often, procedural and bureaucratic issues bog down people’s quest for justice and security”, Dr. Aziz continues. “If, for example, a woman decides she wants to file a lawsuit for rape, then DCVAW not only provides psychosocial support, they also need to prepare and file the lawsuit within 7 days. This too is one of the RBF indicators we have dined in the Context Matters project. We verify this by randomly selecting GBV lawsuits, comparing starting dates of DCVAW case handling, and referral dates to the judiciary. Every unit that scores 100% on this 7-day indicator receives 180 € a month. We have a similar indicator for shelter referral, pushing DCVAW staff to ensure fast protection when women’s lives are at risk.”

More female police officers are needed

The availability of female staff is yet another aspect that touches on issues of confidentiality and integrity. “DCVAW stations still are male strongholds. 80% of the staff are men. This is why one of the indicators for payment is that at least 50% of the cases should be handled by men. In the first verification round we have had, 2 out 3 three units managed to reach that target. It is a first step towards the ideal situation where every woman can have a female officer to handle her case if she wants to. But for Iraq, with its male-dominated culture, this is a big step”, concludes Alwand Talaat.

RBF: changing things instead of waiting for money

Talking about achievements, Dr. Aziz points out the game-changing effect of the RBF approach already has on DCVAW’s workings. “Sure, the RBF approach offers enticing financial incentives. But the effect of these Skinner-like rewards is more than economical. In my last meeting with the overall DCVAW director, she told me that Context Matters has learned them to understand their limitations and to improve, not because a donor wishes them to and pays for it, but out of their own will.”

“This is the opposite of the traditional donor ‘spoon-feeding method’”, adds Alwand Talaat. “By providing an incentive after the outcome has been achieved, they first need to prove their value and depend on themselves. Take the issue of confidentiality. When it was first raised – not by us but by community members during gatherings – DCVAW’s first reaction was ‘we can’t solve this because we haven’t got the money to build extra rooms. By thinking out of the box, by no longer waiting for third parties to come with money, and triggered by the possibility of a financial incentive, they found a way of creating these privacy proof spaces, and even better ways of protecting data and files, simply by using available resources in a different, more responsive way.”

Staying in business during lockdowns

There’s one achievement Alwand Talaat does not want to leave unmentioned. “All through the COVID-19 pandemic and the months of lockdown, the project continued and DCVAW remained functional. Reaching out, adapting to the situation by reinventing themselves and setting up new initiatives like the hotlines and increased use of online media. Once we were no longer allowed to organize workshops and meetings, we switched to online communication tools. Most police officers aren’t familiar with these media and tools, yet they proved to be fast learners. Luckily, NGO staff involved in Context matters like myself and Dr. Aziz were allowed to travel during the lockdown, provided we stuck to all hygiene and prevention rules .”

‘Today, all stations we work with have separate and privacy-proof interview rooms. Each case has one dedicated DCVAW officer. Hotline staff assures anonymity.’

Staying in business during lockdown was of extreme importance. “ Lockdown months saw an increase in domestic violence. And women have fewer opportunities to escape ”, Talaat explains. “That’s where the hotlines proved their worth.”

Breaking the seals of GBV silence

Just over half a year into the project, it’s too early to assess the full impact of Context matters in Iraq. “But what we can say”, concludes Nikki de Zwaan, “is that working with an RBF-approach in the triangle of DCVAW, police, and communities, bears fruit. It helps public service providers to overcome some of their limitations, women to overcome their distrust towards authorities, and communities to break taboos and seals of silence. This increase in trust makes authorities and families alike less prone to sweep the plague of gender-based violence under the carpet of fear and impunity.”